It's never too early to start

For biotechs developing an asset for a pharma partnership, it’s crucial to consider the key deal-success ingredients, in the eyes of a future pharma partner, well in advance. It’s all too common that companies seeking to out-license a new development product, discover too late that there is little to no interest from prospective partners, as the asset does not meet the minimum criteria necessary for a transaction. The result can be catastrophic, as frequently at that that stage there are no longer sufficient financial resources to generate fresh compelling program data.

Target Licensing Profile

The role and importance of a Target Product Profile in strategic planning and valuation analysis cannot be understated - something we discussed in a previous paper. The classic TPP represents the “destination” of a project in terms of specifying the key parameters the new product must meet at launch in order to be clinically and commercially viable. In an analogous manner, we suggest that companies also establish another profile: the Target Licensing Profile (TLP). The TLP defines the minimum set of characteristics and evidence that would enable a drug in development to be of meaningful partnering interest to Big Pharma/Big Biotech.

The elements of a TLP should include the following items:

- Well-defined therapeutic hypothesis backed up by internal data and external publications, with a credible link to the differentiation goal and value proposition.

- Minimum development stage data required for partnering interest.

- Preclinical proof of concept data including sufficient in silico and in vitro data as well as in vivo data from relevant model systems. The data package must show reproducibility, dose-response characteristics, positive controls (also with multiple dose levels), as well as negative controls. Preliminary safety and PK/PD data is also useful.

- IND-enabling data (or plans, depending on development stage).

- CMC information including process description, manufacturing data/plans, a description of a route to commercial scale, and a rough estimate for COGs (clinical dose notwithstanding).

- Clinical data (and/or plans,). Protocols or synopses must be well conceived and sufficiently powered. Thought must be given to dose-ranging studies, which are often forgotten or treated too lightly by many biotechs.

- Strong intellectual property position, with robust market exclusivity prospects in major geographical markets for at least 10 years beyond estimated date of launch.

- Commercial analysis; the depth of this will depend on stage, but at the very least there should be descriptions of the following:

- Epidemiology/treatable patient population;

- Current standards of care including diagnostic pathways, disease/patient staging, lines of therapy, non-drug options, etc;

- Key unmet therapeutic needs, now and anticipated in the light of pipeline products being developed by competitors;

- Estimated pricing and reimbursement corridor.

What Program Data Will Drive a Deal?

The most important assumption in a TLP is the type of data that will be needed to get prospective partners excited enough to do a deal. This is not just the development stage that must be reached, but should also include details such as types of animal models, endpoints, duration, comparators, and effect size. If a company aims too low, they will likely have to leave the deal table to perform the missing study(ies), which may be a financial challenge and require an explanation to investors. The consequences of aiming too high can be a delayed exit or injection of non-dilutive funding, while requiring bigger budgets. Though, theoretically, the additional data should drive higher deal terms.

There are several approaches that can be used to assess the data needed for a future deal, but all have their limitations and should be revisited on a regular basis. These approaches include:

- Analyzing recent deals: Look at the stage of development for analogous programs licensed by others, ideally drugs with the same or similar mechanism and/or aiming to treat the same disease. Don’t forget that every deal sets a new precedent for the buying universe, and companies will accept more risk (less robust data), in order to be first or second in class than they will for an nth-to-market “me better”.

- Asking current players: Although it is important to remember that “first impressions last” in BD, it can be quite informative to pick 2-3 commercial-stage companies with marketed drugs in the target disease indication and ask them what data would get them interested. This approach is not without risk and may give those companies an early read on a biotech’s potential strategy, but the request can be framed in such a way that it is not too revealing. Don’t forget that these responses can vary from person-to-person, from company-to-company, and over time.

- Conducting market analysis: For a mature or crowded market, it is sometimes fruitful to assess the unmet medical need and competitive landscape to deduce what data would likely impress companies. Efficacy in a drug-resistant population, or the first drug of its kind without a certain side effect, or a step-change in convenience, are examples of product benefits which market awareness can identify. Cleverly designed preclinical studies using market insight can also give confidence in the potential for positive clinical differentiation, and sometimes be the trigger for an early stage deal.

- Performing a valuation analysis: It is possible to look at the change in program value as it moves from one development stage to the next with a risk-adjusted NPV analysis. This can reveal an obvious tipping point between cost, risk, and value at which the licensor will need to spend significantly more to do a deal. Such quantitative analysis can indicate the optimal point in development for a partnership. Alacrita is highly experienced with valuation analysis of drug development programs and we use our bespoke value model incorporating Monte Carlo simulation to manage program uncertainty.

Check for Partnerability, at the Start

A first step in the asset partnering process should be a mock due diligence (DD) by a multidisciplinary team (something we frequently perform). This serves multiple purposes: it provides an in-depth understanding of the asset so one can determine the best way to pitch it, it underpins a gap analysis and it identifies the key risks (and possible mitigations) in the program. It provides insight into the questions a prospective partner will most likely raise should they show sufficient interest to enter their own DD and provides an opportunity to define answers (or even design/conduct appropriate studies in advance). It also provides an opportunity for a go/no-go decision point for the main partnering process, should it be judged that the chances of a successful transaction are too low, creating an opportunity to terminate or suspend the process before significant resources are expended. Furthermore, it prevents premature exposure of the asset in an unready state, which is important to prevent negative first impressions from tainting future initiatives. Of course, this spot check on readiness for partnerability may not be needed if the sponsor has previously developed a TLP and brought the program forward in development to the point described in the profile, having checked TLP assumptions regularly along the way.

Deal-Likelihood Framework

Even with a strong TLP, and an asset that meets or exceeds all of the parameters, a successful deal is by no means guaranteed, as there are numerous environmental factors in play. Prior to initiating formal partnering activity, it may also be worth assessing the probability of a deal going through to completion based on the “temperature” at the time (see previous paper: “Beyond rNPV Valuations”). Here are some of the factors that can influence the chances of a transaction for a specific asset:

- Stage in the financial cycle;

- Fit with current market trends;

- Asset uniqueness (TLP should make this more likely);

- Competitive threats (including indirect);

- Size and motivation of buyer universe;

- Execution quality;

- Transaction readiness.

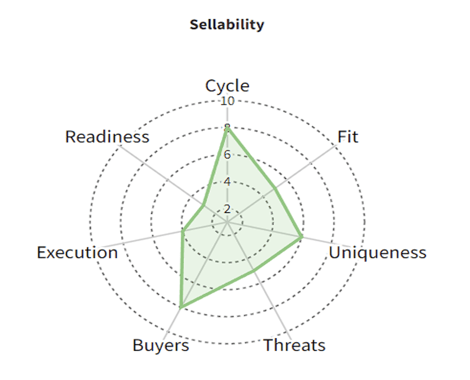

These parameters can be assessed and then plotted on a spider chart (along the lines of the one below), and each factor can be weighted appropriately to produce a composite deal probability score. This type of analysis can be especially useful for a company looking to decide which of several pipeline assets to focus partnering efforts and budgets on.

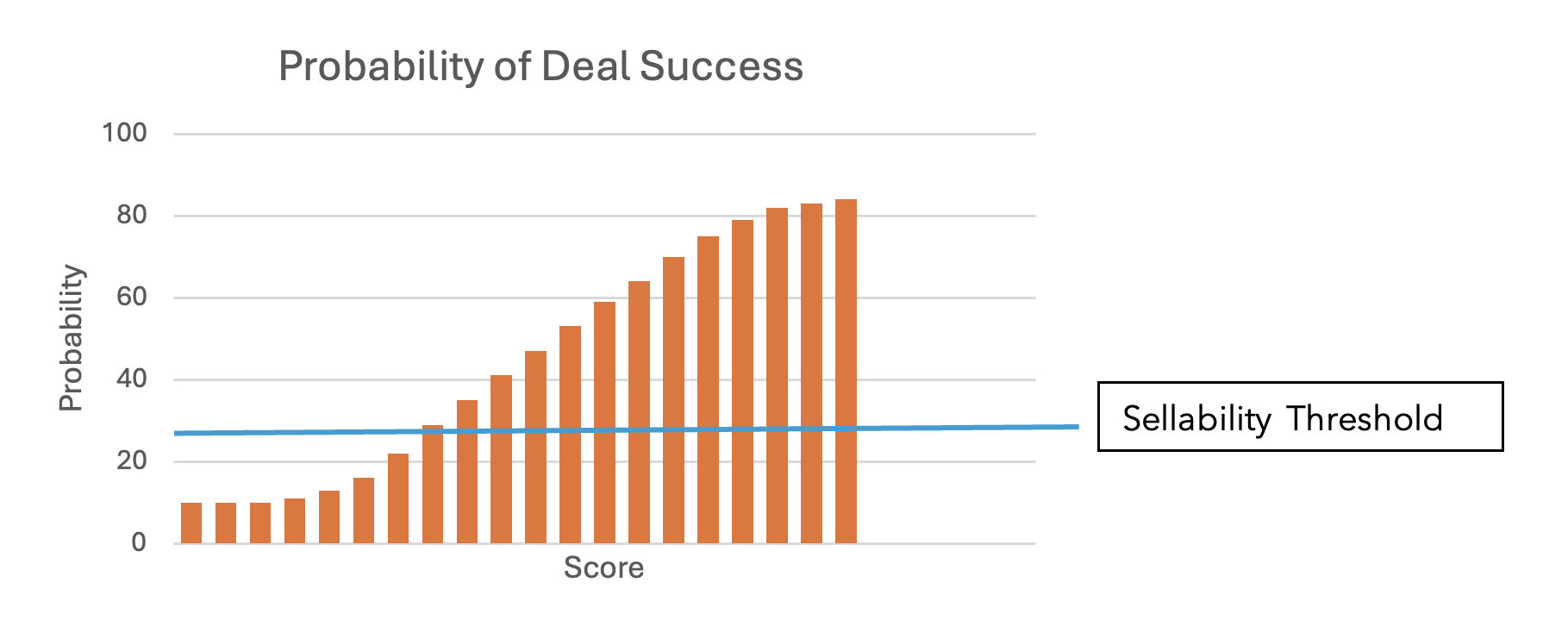

The "sellability" score of an asset can then be charted for interpretation, as conceptualized below. Any situation where the score is below the blue line would be highly unlikely to result in successful partnering.

Conclusion: Solve Problems Before They Occur

In our view, a TLP should be established at the start of formal development activities - several years in advance of the search for a development and/or commercial partner. The act of formulating – and generating internal consensus behind – a destination statement for partnering will provide insights into the scope and depth of studies required to bring the asset to a stage where it is partnerable. As with a TPP, the TLP needs to be regularly reviewed and updated in the light of evolving internal data and external competitive developments; success in a competing program can easily render a TLP obsolete, and internal failure to meet pre-defined TLP thresholds may result in the project becoming non-viable. If such is the case, it is always better to fail fast and divert resources elsewhere than to continue plowing ahead futilely. The evolving TLP can also have major implications for financing strategy. For example, if it becomes obvious that prospective partners will no longer be satisfied with a complete preclinical package, wanting also to see Phase 1 safety data, that’s another 12 – 18 months and likely several million dollars. For these reasons, we strongly recommend biotechs maintain active dialogue with their investors, assess partnerability early, and update it regularly, to set their program on the best possible path to a successful partnership.

About the Authors

- Alastair Southwell, Managing Partner: Alastair brings 25 years of strategic planning and product commercialization experience across multiple disease areas in large pharma and start up environments. He leads our partnering & dealmaking practice. Learn more

- Anthony Walker, PhD, Managing Partner: Anthony leverages more than 35 years of experience, including over a decade spent building & managing a biotechnology company and over 20 years as a management consultant to the pharmaceutical & biotech industries. Anthony leads Alacrita's due diligence practice. Learn more

More About Our Partnering Services

We provide a range of pharma partnering services, including strategy and planning, partnerability assessments, valuations, mock DD's, negotiation support and deal analyses, among other services.